Singapore’s Toughest Prison

Death is the courtesy extended to you as a mercy.

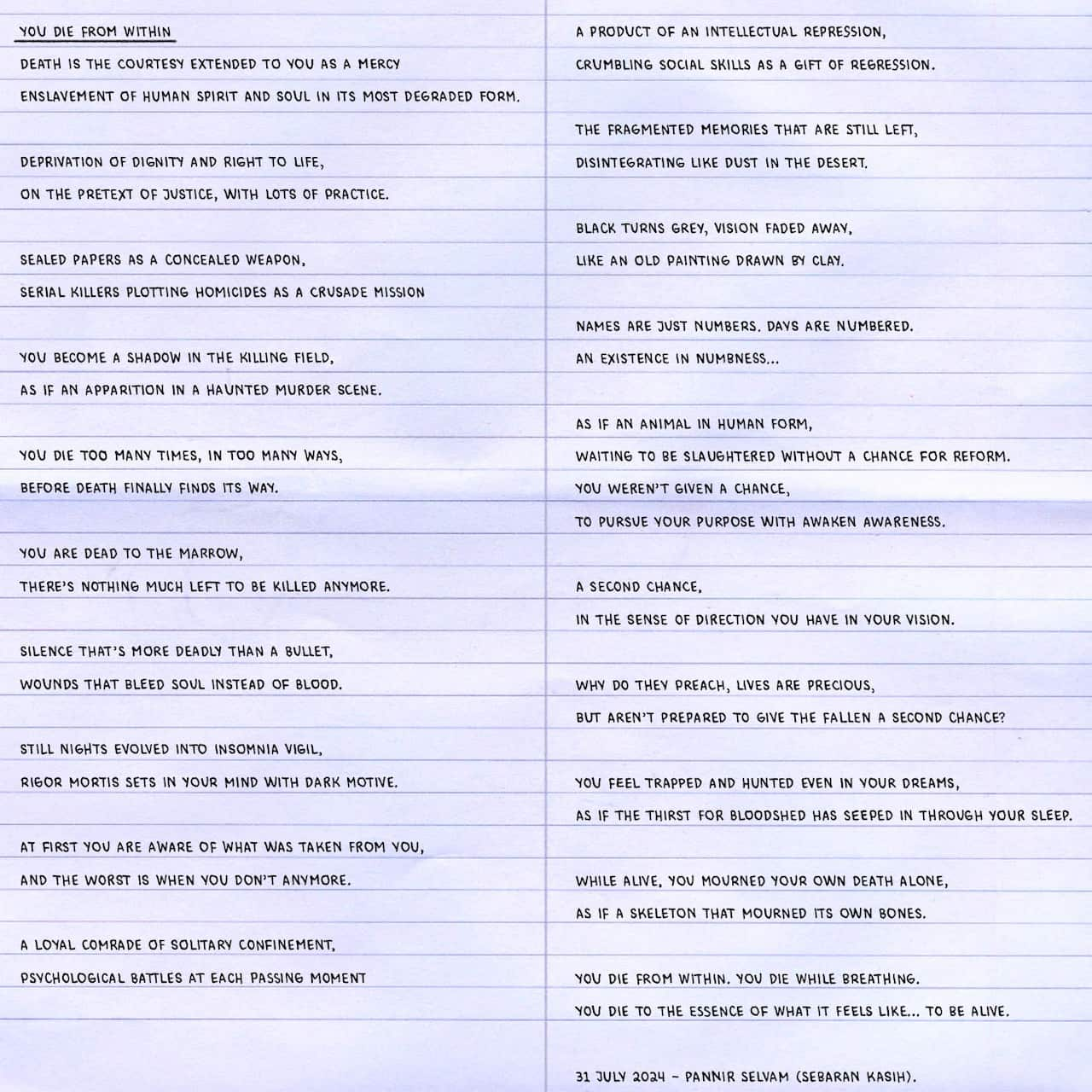

This is the first line of a poem called You Die from Within, written last year by then 37-year-old Pannir Selvam Pranthaman while on death row in Singapore.

Pannir was convicted of smuggling drugs after 51 grams of pure heroin were found on him at a checkpoint on Singapore’s border with Malaysia. According to Singapore’s Central Narcotics Bureau, there were three packets of a “granular/powdery substance” found on his body and one packet in a compartment on his motorbike.

It was his first criminal offence, but in May 2017, he was sentenced to death.

For more than eight years, Pannir, his family, and activists fought to change his sentence, believing it was not proportionate to his crime. But on 8 October this year, he was hanged by the Singaporean government — the twelfth execution this year.

Dateline met Pannir’s sisters Sangkari and Angel in 2024. They would regularly travel six hours from Malaysia to Singapore to see their brother.

“I feel Singapore is being too strict when it comes to drug-related issues,” Sangkari told Dateline at the time.

“They need to give a second chance to first-time committers.”

Both sisters felt that Pannir’s punishment didn’t fit the crime he was convicted of.

“If Singapore [was] really concerned about the people and their safety, they should focus more on the kingpins,” Sangkari said.

Sangkari and Angel fought for their brother Pannir’s sentence to be changed. Credit: SBS Dateline

Kirsten Han, a journalist and activist who works with the families of inmates on death row, said Pannir’s family had worked “incredibly hard” to save his life, including campaigning, lobbying politicians and meeting with media and NGOs.

Since Pannir’s execution, Singapore has hanged two more convicted drug traffickers.

According to Han, one was the only woman on death row. A spokesperson for Singapore’s Ministry of Home Affairs told SBS Dateline that it does not publish information about people currently on death row.

In a statement to SBS Dateline, a spokesperson for Singapore’s Central Narcotics Bureau said: “CNB confirms that a man and a woman, both Singaporean, had their capital sentences carried out on 15 October 2025.”

There have been 14 executions in Singapore this year.

Singapore’s war on drugs

Over the past two decades, more than 400 people have been executed in Singapore, mostly on drugs charges.

The country’s laws prescribe the death penalty for anyone found carrying more than 15 grams of heroin, 500g of cannabis, 1,000g of cannabis mixture, 200g of cannabis resin, 30g of cocaine, 30g of morphine and 250g of methamphetamine.

In certain circumstances, a court may sentence a person to life in prison rather than death for being found with the above quantities of drugs, according to Singapore’s Misuse of Drugs Act. Those circumstances can include the public prosecutor certifying that the person has “substantively assisted” the Central Narcotics Bureau with “disrupting drug trafficking activities”.

Amnesty International reported that in seeking clemency, Pannir had argued he provided the authorities with “substantive information”, but he wasn’t granted the certification that could have seen his conviction changed.

In 2019, Pannir applied for a judicial review of this decision, but it was dismissed by Singapore’s court of appeal.

In August 2025, convicted drug trafficker Tristan Tan Yi Rui had his death sentence commuted to life imprisonment, although official statements don’t indicate it had anything to do with information he provided.

It’s believed to be the first instance of such a death-row inmate in Singapore being granted clemency since 1998.

Both the United Nations special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary killings and Amnesty International had called for Pannir’s execution to be stopped. His execution had been stayed twice already, once in 2019 and once in 2025.

“Pannir’s case is emblematic of the many flaws in the use of the death penalty in Singapore,” said Chiara Sangiorgio, death penalty adviser for Amnesty International, in a statement posted to the organisation’s website.

“Under international law and standards, the imposition of the death penalty for drug-related offences as a mandatory punishment is unlawful.”

According to Amnesty International, in 2024, only four countries executed people for drug-related offences: Singapore, China, Iran and Saudi Arabia.

Malaysia, Singapore’s neighbour, removed the mandatory death penalty for a range of crimes in 2023, resulting in hundreds of death sentences being commuted, although judges there can still impose capital punishment.

Singapore has repeatedly defended its policy of capital punishment for drug offences. It also prides itself on offering rehabilitation for certain crimes, including for drug users.

But in the wake of his death, those who knew Pannir want to make it clear that he was much more than the offence for which he was convicted.

How people feel about the death penalty

In a May 2025 response to Australian media reports questioning Singapore’s approach, the country’s high commissioner to Australia, Anil Nayar, defended its drug laws.

“Singapore is particularly vulnerable to the menace posed by drug trafficking as a small country with a small population. We are at the doorstep of the Golden Triangle — a region which the United Nations described as ‘literally swimming in methamphetamine’,” he said.

The statement also rejected criticism of the use of the death penalty, even in the case of relatively small quantities of drugs being smuggled.

“The quantities may be small, but the impact is not,” he argued.

Nayar said studies of Singaporeans found the majority of people agreed the death penalty was an effective deterrent to drug smuggling.

But activists like Han argue that public support for the death penalty is ultimately a result of pro-death penalty media and a lack of media freedom.

Reporters without Borders ranks Singapore at 123 out of 180 countries for press freedom.

Anti-death penalty activist Kirsten Han says criticsm of the death penalty is not often discussed in mainstream media. Source: SBS / Adam Liaw

“Critical perspectives on the death penalty don’t make it into the mainstream media … you’re generally only getting government statements that the death penalty is working really well,” Han said.

She said the government will then publish survey opinions on whether the death penalty is working “and then they use that public opinion survey to justify that the majority of Singaporeans want to retain this system”.

Pannir’s life on death row

When Han first spoke to Dateline in 2024, she said that there’s “no killing quite like capital punishment, because the death penalty is murder dressed as administration”.

After Pannir’s death, she told Dateline that the government language used to describe drug traffickers often includes “very dehumanising rhetoric”, like calling them ‘proxy murderers’.

In Pannir’s poem You Die from Within, one line describes living on death row like being “an animal in human form”.

Han believes dehumanisation is essential to support of the death penalty.

“[The government] can only get away with this by being highly dehumanising because otherwise people will see it for what it is, which is that they are killing people,” she said.

She described Pannir as someone who worked “very hard to make it clear that people are more than the mistakes that they have made, and that there’s capacity for change, there’s capacity for growth, there’s a lot of potential”.

While on death row, Pannir began reading and writing, even publishing a poetry collection.

You Die from Within is a poem Pannir wrote in July 2024. Credit: SBS Dateline / Caroline Huang / Text supplied by Pannir’s family.

After his execution, when Pannir’s family collected his things, they were given a number of documents, Han said.

“Part of the belongings that were handed over to them was actually his handwritten manuscript for a second poetry collection that he wanted to get published.”

Looking forward

Han is concerned by the high number of executions that have taken place in 2025, and the levels of anxiety that prisoners on death row must feel.

People are executed based on the date of their sentence, which means prisoners know where they are in the ”queue” for execution.

“I’m still a little bit worried about whether we’ll be hearing of more execution notices this week for the coming weeks, and that’s possible. And I think if I’m worried about this, we can only imagine the level of anxiety on death row.”

While media cannot speak to people on death row in Singapore, Pannir’s poetry provides some insight into those feelings.

Why do they preach, lives are precious / But aren’t prepared to give the fallen a second chance?