Simon Archer says the Isle of Man is steeped in stories.

The British-born reverend moved to the island approximately two-and-a-half years ago, attracted to its unique scenery.

“We spent a lot of our time living in London but spending every spare moment we could travelling out of London to get to the places where we hike and walk and camp. We love beaches, we love forests and we kind of went, ‘Why are we travelling when we could live in a place like that?'”

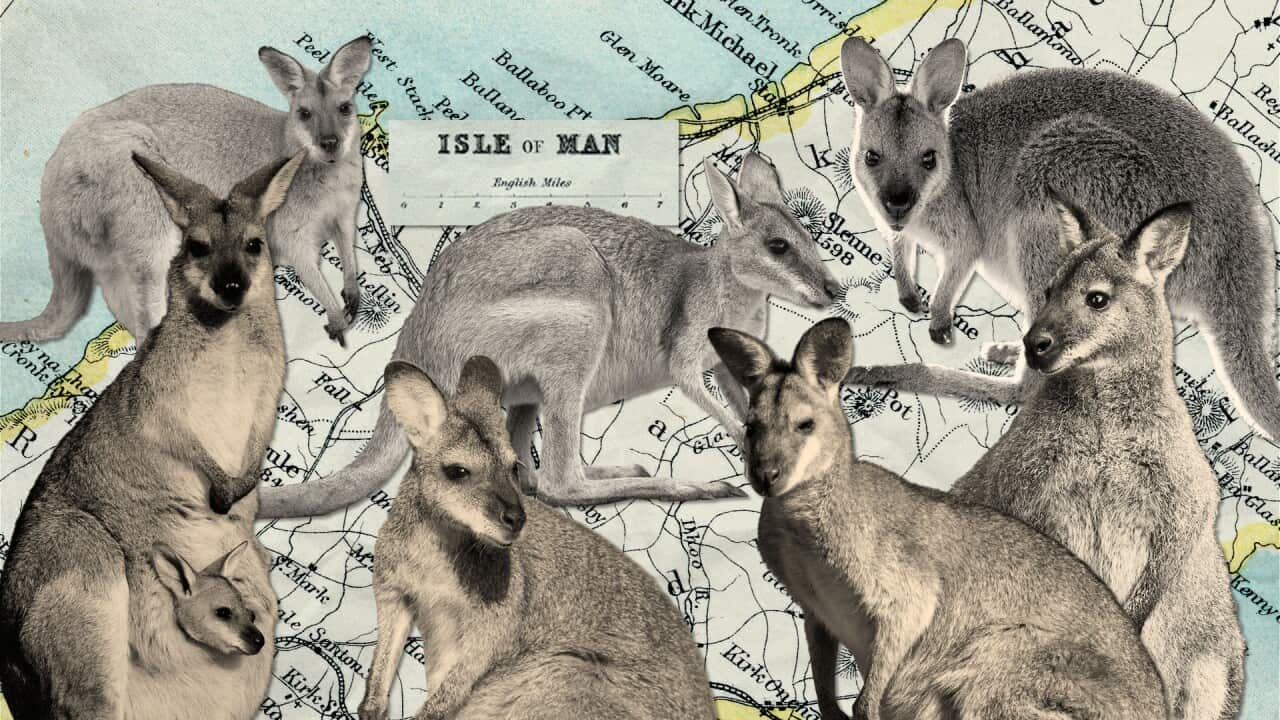

But this remote island located in the middle of the Irish Sea has earned a new — and perhaps unexpected — reputation. It’s home to an iconic Australian marsupial: the red-necked wallaby.

“You start reading the stories about them and the sorts of myths and legends of people who come across them …. [wallabies are] the classic kind of local escapees made good in the environment they’ve escaped into,” Archer said.

The red-necked wallaby earned its name for its distinctive patch of rust-coloured fur. Credit: Sue Corrin

In 2023, drone surveys by Manx Wildlife Trust identified 568 feral wallabies in Ballaugh Curragh, a protected marshland area on the Isle of Man.

Just two years later, the population had grown to 1,000 to 1,300, according to estimates from the local conservation charity.

Anthony Caravaggi, a conservation biologist at the University of South Wales, has been mapping wallaby sightings in the United Kingdom for more than a decade. He conducted a small-scale study using camera traps and statistical modelling.

At the time, Caravaggi thought his estimates of between 1,200-2,000 wallabies on the island were “way off”. But his calculations were consistent with Manx Wildlife Trust’s recent surveys.

“Wildlife can be tricky to spot, if they’re in heavy shrub or some other condition that just makes it difficult to detect them,” he said.

“I do wonder if there was quite a bit missed previously, because otherwise we’re talking about a massive population increase in a very short period of time.”

Wallabies on the run

The exact story behind the Isle of Man’s free-roaming wallabies remains something of a mystery.

It is known that in 1965, a wallaby named Wanda escaped from Curraghs Wildlife Park during its first year of operation. She was returned to the government-owned zoo within a year, but in the decade that followed, more wallabies escaped from their enclosures, according to local media.

Today, there are more than 100 species at Curraghs Wildlife Park, including red pandas, penguins and a population of Australian wallabies. Credit: Curraghs Wildlife Park

The exact number of escapees is unconfirmed, although the gene pool within the population is likely narrow.

“There would be an inbreeding risk, the wallabies may be more prone to disease or the other effects of inbreeding,” Caravaggi said.

Archer, known as the Isle of Man vicar, told Dateline he has varied conversations with parishioners as the local priest at Arbory and Castletown.

“Where I live is … very much a rural farm community and you’ll have people from all different walks of life,” he said.

Archer believes crop damage and the risks associated with inbreeding are key concerns for farmers.

Simon Archer said one of the best-preserved medieval castles in Europe is right on his doorstep. Credit: Simon Archer

“There is a danger that you’re going to have quite ill wallabies wandering around the place … and farmers with livestock understand what that can mean for their animals in the future,” Archer said.

‘Quite damaging’

The Isle of Man has a population of approximately 84,000 people and is a self-governing British Crown Dependency, meaning it has its own parliament, government and laws.

It has a land area of around 500 square kilometres, about the same size as the Vanuatu island of Efate, home to the Pacific nation’s capital, Port Vila.

Ballaugh Curragh, in the Isle of Man’s north-west, is listed under the Ramsar Convention, a treaty aimed at preventing the loss of wetlands worldwide. It’s also been designated an ‘Area of Special Scientific Interest’ by the government, recognising its unique ecological value.

The wetlands are known for their bog pools, birch scrub and grey willow — called “curragh” by locals, from which the area takes its name. With mild winters and cool summers, the habitat also resembles parts of Tasmania, which is where the red-necked wallaby originates.

Caravaggi said winters in the UK are becoming milder and cold snaps less severe.

“We have a lot of shrub … so really, the landscape and the climate are increasingly favourable for them [wallabies],” he said.

And while small in size, wallabies are the Isle of Man’s largest feral land mammal, with a widespread distribution on the island.

In the past, they have collided with vehicles and, in one incident in 2018, caused a car to swerve and crash into a wall.

“They can be quite invasive, they can be quite damaging … and as they grow with no natural predators, chances are that we’re going to come across them a lot more often,” Archer said.

What to do?

Wallabies are considered an invasive non-native species on the Isle of Man. Under the Wildlife Act, it is an offence to release or allow a captured wallaby to escape into the wild.

But historically, the island has taken a hands-off approach to these mammals. Nevertheless, Manx Wildlife Trust has called for an all-island policy on the future of the population, citing their “growing” impact on the island’s ecology.

In an online position statement, the organisation acknowledges there are different views on the way forward, citing calls from some in the community to “cull them all”. It also notes others believe wallabies are “a headline visitor attraction” or “useful conservation grazing animal”.

In their statement, the trust said there are three options to consider — eradication, management or no action. The charity did not respond to further questions from Dateline.

While Archer said he would “hate” to see wallabies culled altogether, he acknowledged they are an invasive species.

“You have an invasive species, basically it’s not meant to be there and however cute and sweet it might be to someone … it’s [eradication is] still something that has to be considered as an option,” he said.

As a scientist, Caravaggi said his perspective on culling the animals would ultimately be driven by the evidence.

“I think we need to close these kinds of knowledge gaps, answer the questions that we have, before we make a statement either way,” he said.

Feral Australian species elsewhere

From redback spiders in Japan, to mosquitoes in urban California and brushtail possums in New Zealand, Australian species have established feral populations worldwide.

Tim Lows is an expert on introduced species and co-founder of the Invasive Species Council. He believes biosecurity is a growing threat and has become increasingly complex to prevent, detect and intercept.

“It’s so difficult to put genies back in bottles. With globalisation, people buying things overseas, going overseas a few times a year, it’s [biosecurity threats are] just exploding,” he said.

Detector dog teams intercepted more than 42,000 high-risk items, including at Australian airports in 2024. Source: AAP / David Jones

The Department of Defence has a budget of almost $60 billion a year. Comparatively, funding for biosecurity is $935 million, which is expected to decline to $889 million in 2028–2029, according to the Australian Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry.

From Lows’ perspective, biosecurity is “underfunded” and should be valued as highly as defence.

“I mean, it’s not a sexy issue,” he said.

But for the humble wallaby on the Isle of Man, which has found itself at the centre of the conservation debate, Caravaggi believes public opinion is “a very, very strong player in conservation now”.

The fate of the animals is yet to be determined, though Caravaggi believes a decision is on the horizon.

“Especially driven by the globalisation of media and social media … my impression is that they’re [Isle of Man] on the cusp of making a decision one way or another.”