In a marine park along the French Riviera, a mother and son are swimming in circles, waiting for a decision to be made about their future.

Wikie is a 24-year-old orca whale and Keijo, her son, is 12.

Their current home, Marineland Antibes, closed to the public in January, but nearly a year later, the pair are still there.

The park attributed its closure to “serious economic difficulties”, including declining attendance, post-COVID economic issues and, crucially, a law change.

In 2021, the French government banned the captivity and performance of cetaceans: whales, dolphins and porpoises. Marine parks and aquariums were given until December 2026 to find new homes for those already in captivity.

Marineland Antibes tried to transfer Wikie and Keijo to a marine park in Japan, but the French government rejected this based on concerns of insufficient animal protection standards.

The government considered two alternatives: a potential whale sanctuary in Canada or a marine park in Spain subject to EU regulation, but neither plan has worked out. The whale sanctuary hasn’t been built yet and a Spanish scientific agency rejected the transfer.

“There are a lot of facilities … [that are] closing down, and that’s a great first step, and I applaud them for that. But now they need to step up and help care for these animals who they bred into captivity,” said Lori Marino, founder of the Canada-based Whale Sanctuary Project (WSP).

So, the question remains: where should Wikie and Keijo go?

A chance for ‘a dignified retirement’

There are 54 orcas currently in captivity worldwide, across China, the US, Japan, Spain, France, Russia and Argentina, according to global dolphin and whale captivity tracker Cetabase.

As countries start introducing bans on cetacean captivity, another problem is emerging.

Dr Naomi Rose is the senior scientist of marine mammal biology at the Animal Welfare Institute in Washington DC. She’s also on the board of the WSP.

“What happens to all these animals as facilities go bankrupt and shut down?” she said.

Since the French law was introduced, Wikie’s 25-year-old brother Inouk and her 12-year-old son Moana have died in Marineland.

According to Rose, more than intelligence or ecology, the best predictor of how well a species will fare in captivity is how wide-ranging they are — essentially, how far they typically travel.

Orcas can travel hundreds of kilometres a day, regularly diving 20 to 30m below the surface. Rose said the largest enclosures only tend to be around 70m long, 30m wide, and 10 to 12m deep.

Wikie and one of her babies in 2011 at the Marineland park in Antibes, France. Credit: AAP / AP / Lionel Cironneau

Whales born and raised in captivity, like Wikie and Keijo, have spent their lives performing for food. They haven’t had the chance to learn necessary survival skills, so can’t be released into the wild.

The “goal is to provide as many of these animals who are currently in captivity the option of a dignified retirement,” Rose told Dateline.

The potential for whale sanctuaries

According to Rose, there are “well-established” models for wildlife sanctuaries, but these are all land-based. Establishing a marine sanctuary is more difficult.

“You can buy land, you can buy a huge amount of land, a ranch or whatever, and then turn it into an elephant sanctuary. You can’t do that with the ocean. You can’t buy the ocean. You have to rent it, if you will,” she said.

There are currently no sanctuaries capable of supporting orcas.

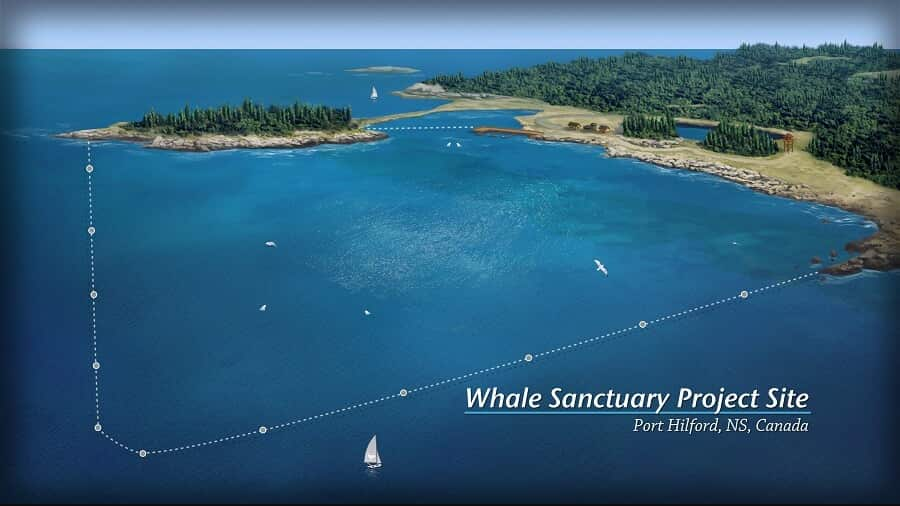

Dr Lori Marino hopes that will soon change. A decade ago, the neuroscientist founded the WSP, which has been working to create the first orca sanctuary in Nova Scotia, a province on the east coast of Canada.

In October, the project was given approval from Nova Scotia’s provincial government.

The next step takes “a lot of money” — she estimates US$15 million ($22.6 million).

A graphic rendering of the proposed whale sanctuary in Canada. Credit: Whale Sanctuary Project

“We know exactly what we need to do to create the sanctuary,” she told Dateline. “We need the whales.”

The WSP consider Wikie and Keijo as potential candidates, as well as belugas from Canada and South Korea.

“We can’t take all of them, but we certainly are working to see if we can provide a sanctuary for some of them,” she said.

But while a French government-commissioned report described it as the “most credible innovative solution”, they found it wasn’t feasible to be ready for how quickly Marineland wants to move the whales, despite an offer of an accelerated timeline for construction.

Why is rehoming whales so complicated?

Public attitudes towards the captivity of whales, and the existence of zoos more broadly, have been shifting over the past few decades.

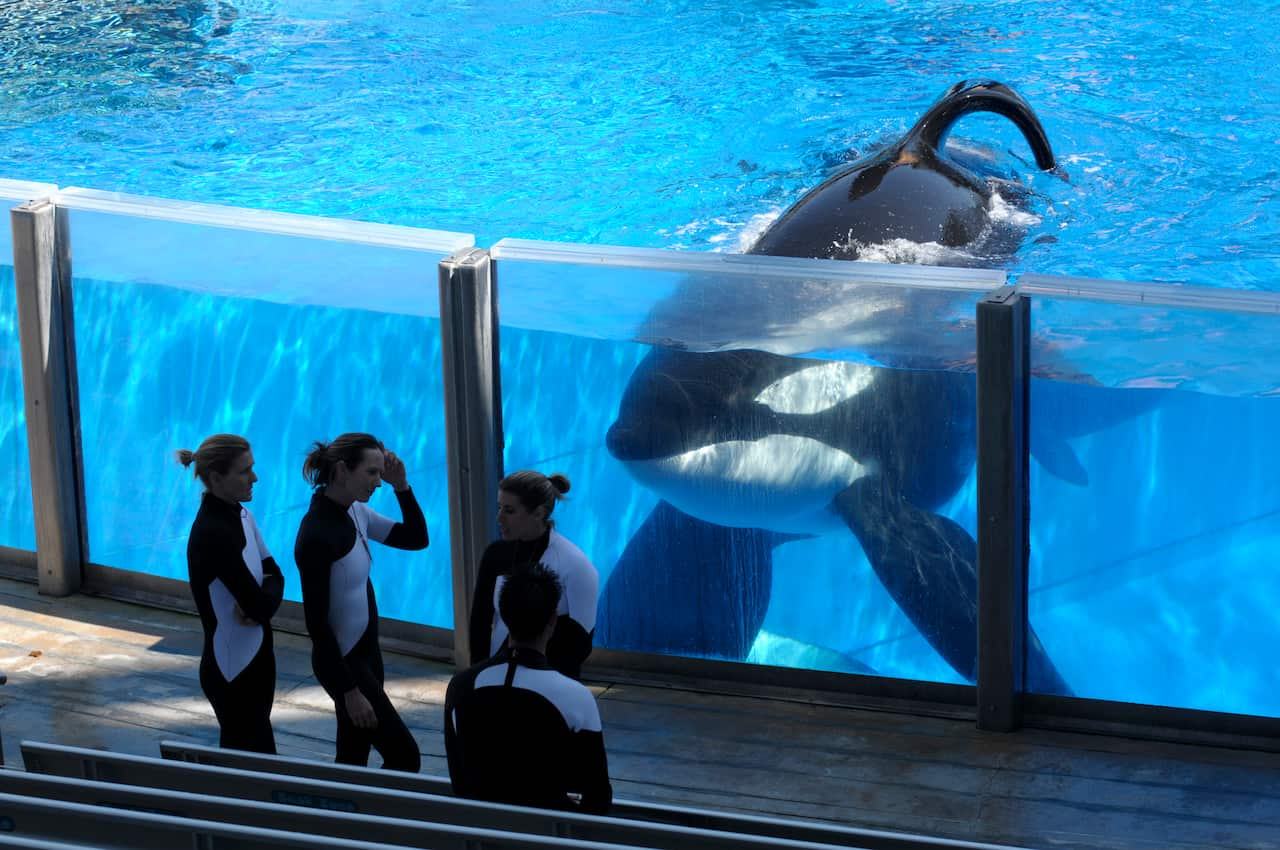

Academic studies have investigated “the Blackfish effect”, the term given to the shift in public opinion after the release of the 2013 documentary Blackfish, which looked at the impact of captivity on Tilikum, an orca whale at Sea World in the US who was involved in the deaths of three people, including SeaWorld Orlando trainer Dawn Brancheau and Sealand of the Pacific trainer Keltie Byrne.

At the time, SeaWorld said, “instead of a fair and balanced treatment of a complex subject, the film is inaccurate and misleading”.

In the wake of the documentary’s release, a campaign to #EmptyTheTanks spread on social media alongside protests outside SeaWorld, as public pressure increased to end orca captivity at marine parks around the world, encouraging the transfer of captive whales to sanctuaries where possible.

Tilikum was one of the orca whales used for SeaWorld’s Shamu show. He was the subject of the documentary Blackfish. Credit: AAP / AP / Phelan M. Ebenhack

SeaWorld ultimately stopped its orca breeding program, announcing their current whales would be the last generation at their parks.

“We’ve helped make orcas among the most beloved marine mammals on the planet,” then SeaWorld Entertainment CEO Joel Manby said at the time.

“As society’s understanding of orcas continues to change, SeaWorld is changing with it.”

Rose said marine parks could make changes to their business models that would allow them to improve the welfare of their whales while still generating profit, potentially through building their own sanctuaries. But they are “very rigid in their idea of what makes a profit”.

Rose said the three main arguments for keeping captive orcas as “ambassadors for their species” are research, conservation, and education. But she said this approach is flawed as global conservation efforts have had limited success.

“Our planet’s been going to hell in a handbasket for the last few decades,” she said.

And in terms of research, Rose said since the captive environment is so different to the ocean, scientific findings aren’t easily transferrable.

Parks argue they educate the public by engaging audiences and encourage them to participate in broader conservation efforts. Rose said the data doesn’t show this.

“It happens once in a while, but it doesn’t justify the suffering these animals go through to make five conservationists.”

From dolphin trainer to whale scientist

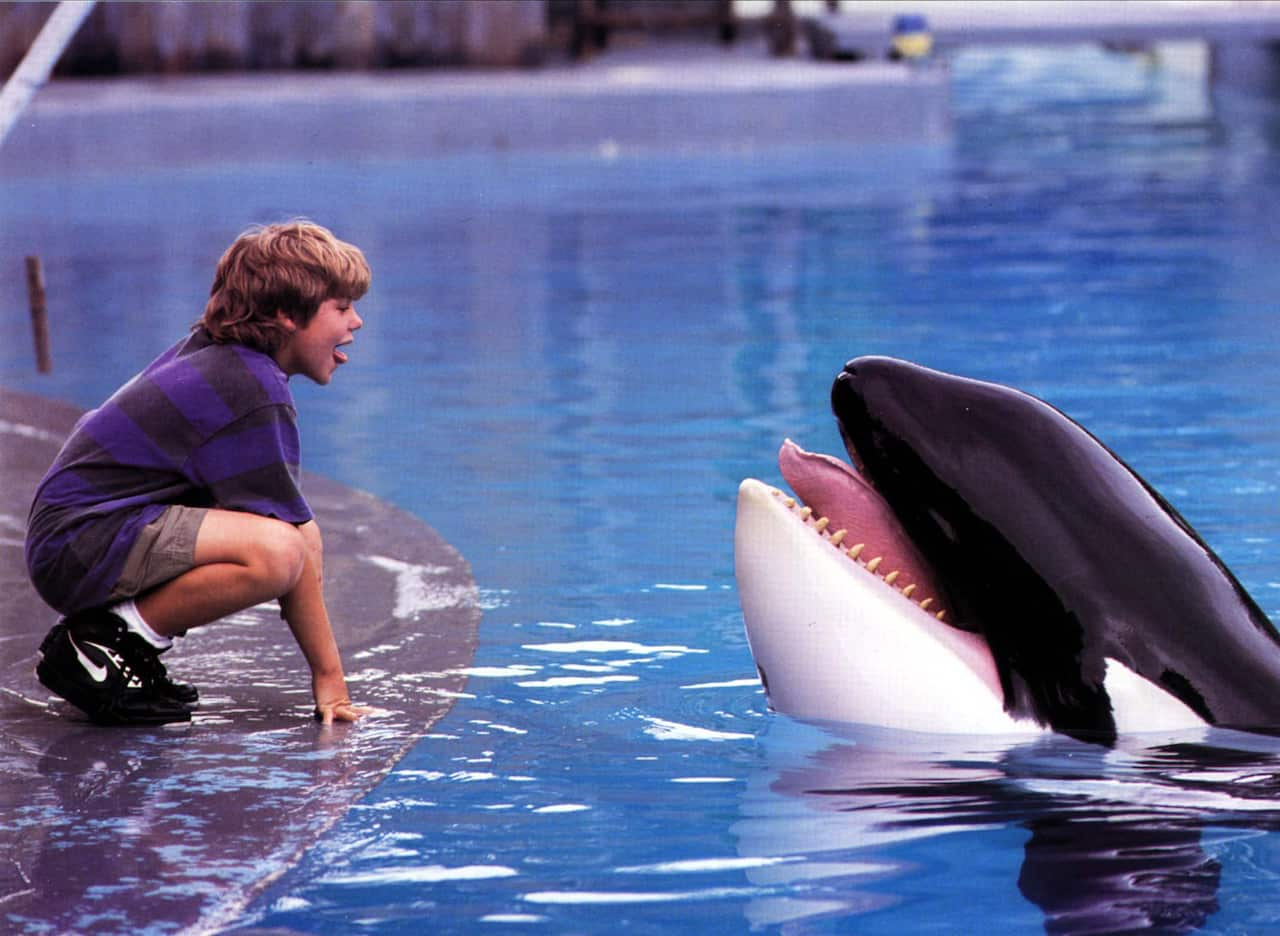

Dr Vanessa Pirotta is a whale scientist at Macquarie University in Sydney. Growing up in Canberra, far from the ocean, she was inspired by the 1993 movie Free Willy.

Before becoming a scientist, she worked as dolphin trainer at a facility in Coffs Harbour, on the NSW north coast.

“There is so much that these places offer, and that’s what I had an opportunity to see and to be part of,” she told SBS Dateline.

The experience also helped her develop skills, from an “understanding of animal biology” to learning how to explain wildlife science to audiences of all ages.

She believes she may not have entered wildlife science without the story of Keiko, the captive star of Free Willy whose controversial return to the ocean is still debated more than two decades after his death.

After the success of the 1993 film Free Willy, Keiko the whale — who had been in captivity since age two — was released into the wild in 2002. He died a year later of pneumonia. Credit: AAP / Mary Evans Picture Library

She doesn’t want to see more wild animals captured for facilities like marine parks.

“As a scientist, I don’t agree with the capturing of any further animals into captivity,” she said.

However, Pirrotta said she thought people also tend not to understand that zoos can have an important role in caring for rescued animals, rather than just existing for entertainment.

“There is largely a discrepancy of understanding of the pros and the cons of captivity… it’s very tricky,” she said.

As a former trainer, Pirotta said it’s important to remember that facilities have a duty to continue providing for animals in their care “so they can see out their life in the best way possible”.

In some extreme cases, she said, euthanasia may be the best option.

“The reality is these animals are also long-lived, which means that a small pool of money may sustain a period of time, but may not be ongoing,” she said.

While lifespans vary between captivity and the wild, Corky, the oldest captive orca is in her late fifties and has lived at SeaWorld San Diego for more than 30 years.

Thirty belugas under threat of euthanasia

Similarly to France, the Canadian parliament passed a law in 2019 to restrict the future captivity of whales and dolphins.

Camille Labchuk is an animal rights lawyer and the executive director of advocacy group Animal Justice Canada. She was part of the nearly four-year campaign to change Canada’s laws.

She said the idea of the law was that “the generation in tanks now would be the last generation”.

Marineland of Canada (no relation to Marineland Antibes) closed to the public in September 2024. Thirty beluga whales still live there.

Belugas at the Marineland of Canada marine park, pictured here in 2012. The park stopped operating in 2024. Credit: Gett Images / Tara Walton / Toronto Star

An application to transfer them to a Chinese marine park was rejected after concerns they would return to performing in captivity.

Citing the cost of continuing care after the park is closed, the operators have said, in a letter to the Minister of Fisheries, their “only options at this point are to either relocate the whales or face the devastating decision of euthanasia”.

Labchuk said it is legal if Marineland doesn’t kill them “in a cruel manner”.

However, she doubts there is a way the whales could be killed “without delving into criminal animal cruelty”.

She said solving the issues of rehoming animals in captivity would require a “concerted international effort” and called on politicians to support whale sanctuaries.

“The world has plenty of coastline. The world has plenty of goodwill.”

What does the future hold for France’s trapped orcas?

In their assessment of potential destinations, the French general inspector for the environment said Wikie and Keijo must be moved in 12 to 18 months to avoid exposing them to “excessive risk”.

That recommendation was given 18 months ago, in June 2024. No solution has been reached yet.

Marino said the WSP is still working to take the pair.

“We’ve been having some very open, very substantive conversations with [the French government] about Wikie and Keijo,” she said.

“We are hoping that continues to go well and we have the opportunity to bring them to Nova Scotia.”